I’m a white guy with a beard and a humanities degree. I like going for walks. It was inevitable, then, that I’d find my way to psychogeography.

It’s a practise (or set of practises, I guess), that I’ve been aware of for a long time but haven’t engaged with in a serious way. I read The Society of the Spectacle around the time the Leveson enquiry was happening and felt very knowing. I’ve recently felt compelled to take more and more notes in all areas and aspects of my life, and one of those areas has naturally been the walks I take around the Peterborough area.

But more on that later.

Happenstance, serendipity, chance. Call it what you will, it plays a bigger part in our lives than any of us can admit and stay sane. The stakes aren’t always super high, though. I was thinking about Iain Sinclair and how London Orbital was such a great idea for a book because I had seen people discussing it on Twitter. I was thinking about it as I walked in to a charity shop and immediately spotted a copy of it on the shelf.

(I know what the Baader-Meinhoff phenomenon is.)

I started it pretty much immediately but it’s taken me a good while to work through. I get the impression Sinclair does not write nice easy books about his nice easy travels. His project, to walk a circuit of London directed by the M25, within its “aural boundaries”, and to get it done before the Millennium, was a difficult, stop-start task, and London Orbital is a difficult, stop-start book.

A lot of it is down to Sinclair’s writing style, which is one of those where you have to glom on to the rhythm and tone and go with it, as opposed to fighting it and trying to decipher every sentence exactly. In a lot of ways Sinclair is non-fiction Ballard, obsessed as he is with the same spaces, the same processes, but in terms of style and tone, it’s more like Virginia Woolf’s writing about London, or Hope Mirrlee’s Paris. You are absolutely in the stream of Sinclair’s consciousness. As much as he is reporting facts about where he walked, when, who with, he’s also recording his impressions, snatches of conversation, bits of text he sees on the streets, adverts, digressions about the history of literature and the history of London.

It’s great and I love it and I found myself going with the flow quite quickly, even if I couldn’t always abide it for very long, but I can imagine someone struggling and getting out and not coming back.

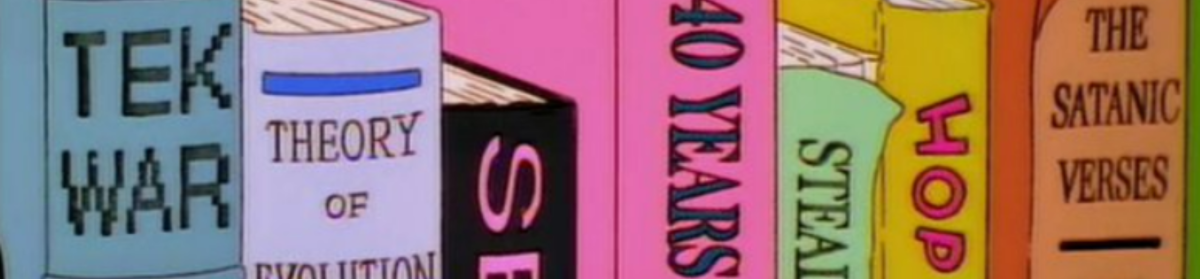

The digressions are fascinating. I suspect some of these projects Sinclair engages in are ways of him bringing his enormous reading to bear in a context that will stand it, and who can blame him? What’s particularly interesting, I think, is the way he doesn’t make much of a distinction as to fact or fiction. A house William Blake might have stayed in is treated with the same weight as an area that plays a part in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. And why not? It weighs just as heavily in the imagination, especially if you’re there. The few pages on Dracula stunned me; Sinclair describing him as the original psychogeographer, as map obsessive, London obsessive, someone already forming deep and psychic connections with a space before he’s even arrived. It’s an angle I’d never considered, and it’s made me immediately want to go and re-read Dracula. It’s almost throwaway how Sinclair introduces the idea and it’s better, more original, more interesting literary criticism than I’ve seen in ages.

(If the idea comes from somewhere else, or has an antecedent, please let me know in the comments.)

I imagine you have to be careful, writing non-fiction featuring your friends, to not abuse their good nature or turn them in to figures of fun. I always loved the way Bill Bryson talked about his relationship with his friend Stephen Katz in A Walk in the Woods and thought it a model for that kind of thing. Sinclair walks the same tightrope and succeeds here. In particular I’d highlight his portrayal of Kevin Jackson, who comes along on some stretches of the walk totally unprepared, or even misprepared, and is treated within the narrative with real sympathy. He brings a jacket that’ll “cook him if he wears it, cripple him if he carries it”. He wears trainers when he should wear boots, and boots when he should wear trainers.

It’s clever, the way he uses these real people as characters. Renchi Bicknell is a foil for Sinclair in the sense that Sinclair is often a detached observer, interested in what these spaces do to his own interior space, whereas Renchi is the people person, the smooth talker, the one who can get them past a security guard or talk down a paranoid local. Kevin, on the other hand, reminds us of the physical reality. Life isn’t frictionless; we have bodies we need to navigate through these spaces. Kevin stops the book becoming about the M25 in Sinclair’s own head, which would be fascinating I’m sure, but also one-note.

If you’ve read any of my reviews before you’ll know the highest compliment I feel can pay a book is that, having read it, I immediately want to go off and write an imitation of it (see Renata Adler’s Speedboat). If you haven’t guessed by now, I’d pay London Orbital the same compliment. I’m ready to fall down the psychogeography rabbit hole.

I can see Iain Sinclair has written quite a few books. Is there somewhere you’d recommend I go having started with London Orbital? Not that I lack for stuff to read, because to pay it another compliment, I’ve come away with yet more on my reading list.

One thought on “Some Thoughts on Iain Sinclair’s London Orbital”